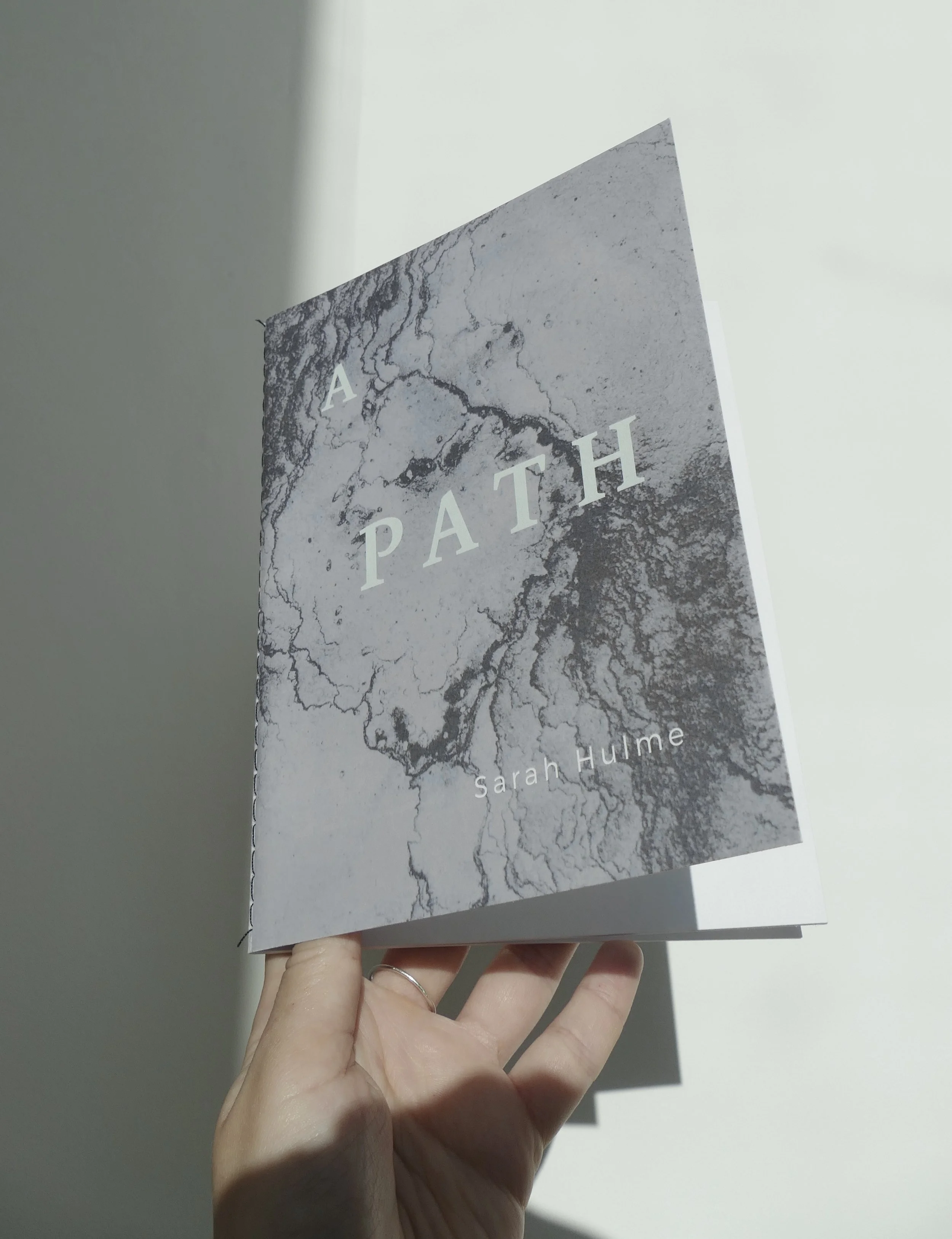

A Path in Focus: Q&A with Sarah Hulme

We are delighted to bring our first publishing year to a close with the launch of Norwich-based poet Sarah Hulme’s spellbinding pamphlet, beautifully illustrated by printmaker Helen Rollinson. A Path is a poetic sequence that explores coastal erosion and mental health. Through the disintegration of form and language, it reveals how truly entangled we are with the landscapes we live in.

Ahead of launch day, we caught up with Sarah Hulme to understand more about the background to the pamphlet and its ideas and influences.

What inspired the sequence, and how did the initial idea take shape?

The idea for this sequence came from Jos Smith’s Poetics of Place module on the Creative Writing MA at UEA, where we were asked to think about the idea of local distinctiveness. Around the same time I walked the Norfolk coastal path and witnessed the extreme coastal erosion taking place — Norfolk has part of the fastest eroding coastline in North-West Europe. I became fascinated by the narratives and voices held together in this liminal space and the tangibility of time. This included things like car park maps showing paths and land that no longer existed, a tarmac road running straight to a cliff edge and a house on the edge of a concave drop that — shockingly — was still inhabited. I became interested in how this rapidly changing place could be mapped by poetry and how poetic process could be seen as a form of erosion and a way to tell this narrative. In particular, the rewriting of a single poem with the loss of words and change of form creating a landscape on the page reflective of a landscape undergoing coastal erosion. Over the course of a year I wrote and rewrote a single poem about the Norfolk coastline which eventually became A Path.

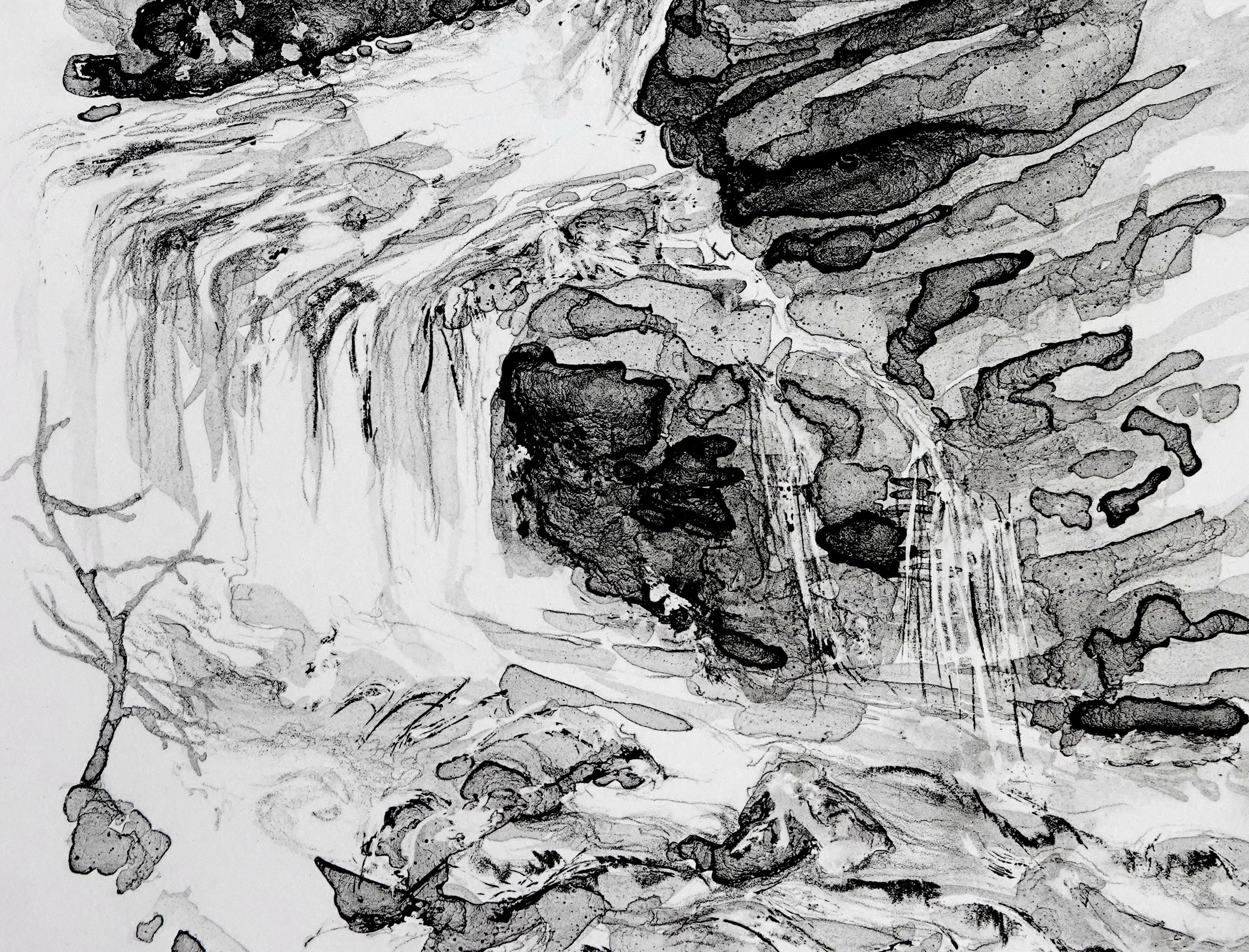

Detail from ‘Cascade’, an original lithograph by Helen Rollinson, used to illustrated the pamphlet.

What role does colour play in the pamphlet?

Colour is used to help tell the narrative of coastal erosion through the shift in the geology of the coastline. The sequence begins with green representing a landscape untouched by coastal erosion with patchwork fields dominating the landscape. It then moves to red as coastal erosion begins to take effect and the green of the fields gives way to the red soil underneath. And finally finishes with blue as the sea floods the land and the landscape becomes dominated by sea and sky. As well as telling the narrative of the geological shift of the landscape colour is also used to represent a deteriorating mind by using ideas of colour theory. The sequence moves from the stability, life and growth of the colour green to the warning, violence and ruin of the colour red to the sadness, loss and calm (in release) of the colour blue.

How do you use language and poetic form to explore mental deterioration?

As well as using colour, the sequence also uses the unravelling of language to portray this deterioration. One way this is achieved is by placing abstract nouns alongside concrete nouns creating a dream-like quality suggestive of a dissociative mind. For instance, the description of the path as “a shout Goodnight!” and “another sunken mind”, the impossibility of a “pebble falling from thought” and phrases such as “rock scream”. This dream-like dissociation is also achieved through the use of sounds. In particular, the use of the same (or similar) sounds hidden in different words and producing different meaning.

For instance, “feel o filo earth o leaf a life” and the progression from,

per

haps said nothing at

all

to,

Perhaps

said nothing a

tall sea

This disorients the reader through a sort of poetic deja-vu as the reader is caught between familiarity (of sound) and newness (of meaning and appearance).

What does the motif of the path represent and who is Wade, and what role do they play in the poem?

The path acts as a guide for the reader as they negotiate the landscape of the page which is haunted — and hunted — by Wade, the Anglo-Saxon god of the sea. Wade represents the power of the sea and threat of coastal erosion to the stability of the landscape and the mental health of those that live in it. Throughout the sequence we follow the path as it shifts in guise as a result of Wade’s erosion. The path moves from a physical, tangible thing to an abstract presence that speaks, not only to a drowned landscape, but a mind in an increasingly dissociated state, ultimately falling into madness.

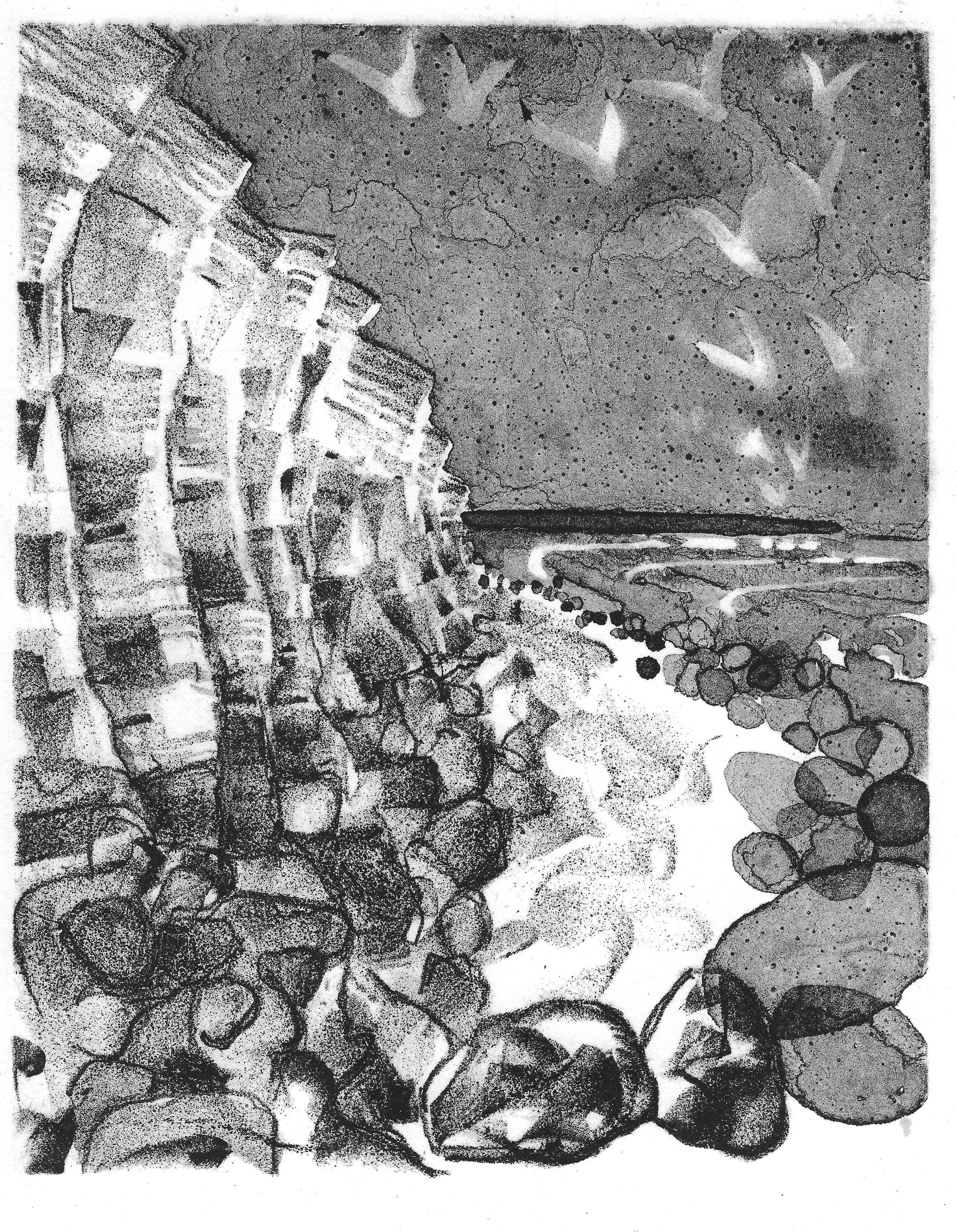

‘At the Edge’ by Helen Rollinson.

You use erasure and the physical space of the page in striking ways. What drew you to these techniques?

The physical space of the page in poetry is something that has always fascinated me. I enjoy experimenting with the full space of the page to create a landscape that the reader can enter into and navigate. This was particularly important in A Path as I wanted the reader to experience the sequence as they might experience walking and returning to a coastal path over and over at different times, finding familiarity in the land — and poetry — but also newness and loss as a result of coastal erosion.

One way this is achieved in A Path is through repetition and erasure. For instance a number of the poems in A Path contain erasures of poems preceding them in the sequence. The repetition brings familiarity to the reader, we have seen this landscape before, whilst the erasure brings loss. Erasure is often done with strikethrough, however I chose to keep the letters; instead ‘erasing’ them by changing the text to white. This puts the emphasis on the loss and the gaps created by erosion, as can be seen by comparing the below segments,

Find me a path through

grene grene grene of

sugar beet bland. This is in

land.

a path rough

grene grene grene o

land in

land.